Everyday Ghost Stories

The traumas and tribulations that make us who we are

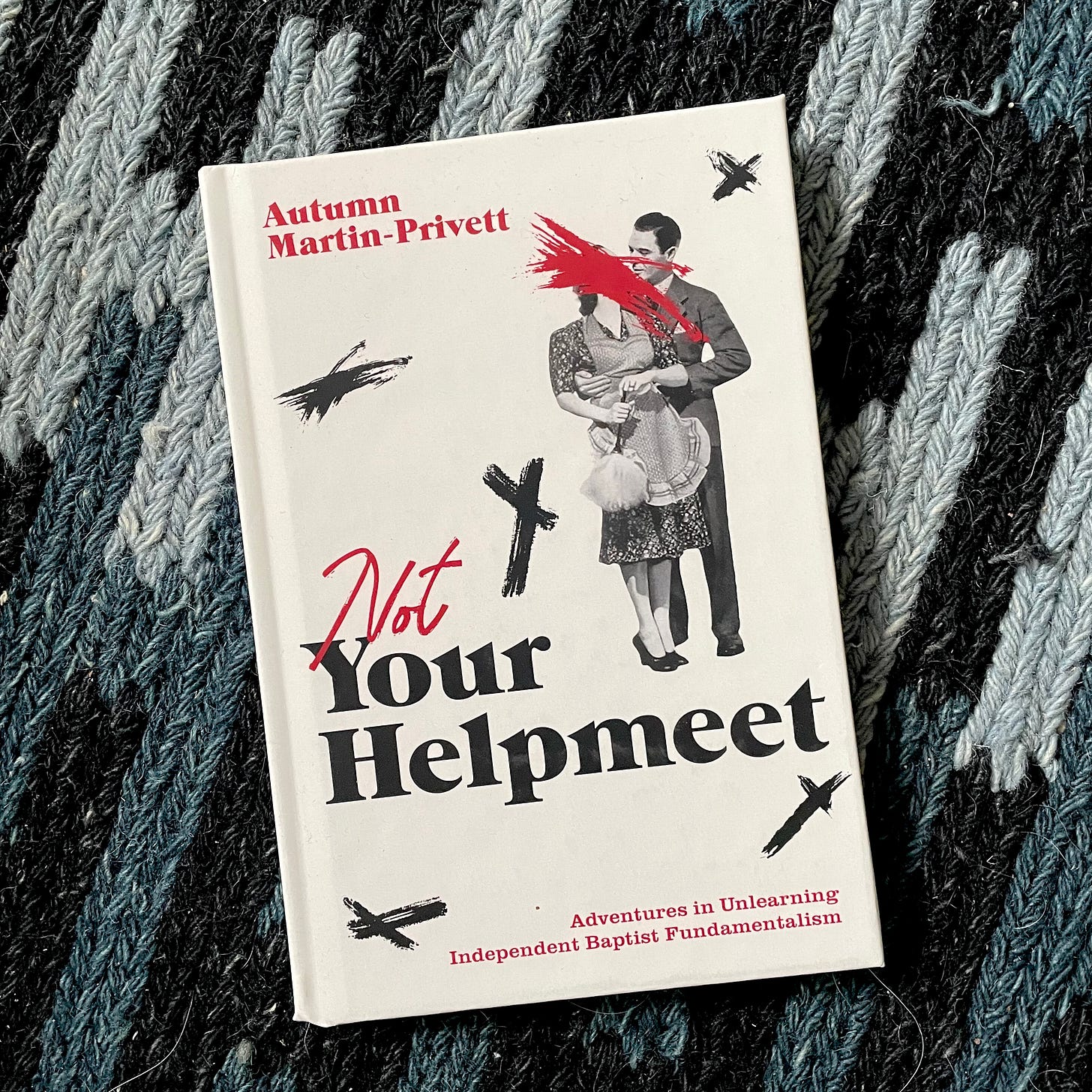

For Christmas, Josh had all the essays I wrote last year bound and printed as a book. As I unwrapped the package and saw the cover, I bizarrely thought he had gotten me custom notebooks to use to write in for the coming year. It was the only way I could process what I was holding. I opened the cover and realized that it was not, in fact, a blank notebook, but my writing. I cried.

I started writing because no one believed I grew up the way I did. In small groups, at job interviews, at parties, people would ask me where I was from or where I went to school, at which point I would try to downplay my past. I would say “a small Christian school you’ve never heard of” or “well, I grew up very religious” and, this being the South, people would assume that I went to some church or college they’d heard of. The further down this rabbit hole we got, the bigger their eyes would get. “I can’t believe things like this still exist”, they would say, explicitly or implicitly. They assumed all Southern church people are the same. To an extent, that’s true, but not entirely.

I started writing my thoughts down in google docs as a way to bear witness to my thoughts and experiences. I squirreled away essays for years, too afraid to actually share them with anyone besides myself. Somewhere during the pandemic, I changed. Perhaps it was the pandemic. Perhaps it was therapy. I decided it was time to out myself as a former Fundamentalist. Writing was cathartic. It helped me think through things I’d been mulling over for years. Or, in the words of Flannery O’Connor, “I write because I don't know what I think until I read what I say.”

As I revisited essays and parts of essays, I began to realize that I am no longer the person who originally wrote those things. I realized that my anger at the people who had misled me and my family had morphed into something less reactionary. I believe in justice, but I’m also done giving that much time and energy to people who don’t deserve it.

There’s a passage at the end of Gabrielle Zevin’s excellent novel Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow where one of the characters talks about not wanting to be defined by their trauma.

“… This generation doesn’t hide anything from anyone. My class talks a lot about their traumas. And how their traumas inform their games. They, honest to God, think their traumas are the most interesting thing about them. I sound like I’m making fun, and I am a little, but I don’t mean to be. …”

“If their traumas are the most interesting things about them, how do they get over any of it,” Sam asked.

“I don’t think they do. Or maybe they don’t have to. I don’t know.”

This passage bothered me. I thought about it for days. How can one bear witness to the things that they experienced without making it part of their identity? The internet wants us to have a niche, so we become “that guy who cuts things in half” or “that person who survived an incredible tragedy.” But we’re all more than that, right?

So much of my time the last decade has been spent trying to make peace with myself. I ran from my Fundamentalist past. Then I took it as a banner. Now, I don’t know.

This idea keeps following me. On This American Life this week, Etgar Keret tells a collection of stories about his mom, who was a Holocaust survivor. In the middle of the episode, Ira and Etgar have this exchange:

Ira Glass

You've told me that one of the things you want to be careful about is you don't want to overemphasize your mom's experience in the war. Explain that. Explain why.

Etgar Keret

Well, you know, I think that there was something about my parents that they felt at the moment that they were seen as Holocaust survivors. They were kind of losing something at this moment. They became less of an individual and more of, I don't know, a symbol. My parents really, really disliked that.

I felt for my mom that the moment that she was seen as a Holocaust survivor, it would be a little bit like a wild horse, that it was as if the Nazis had branded her. She can't take this thing off her, you know? But the moment that she could be this funny, redheaded woman who reads a lot, and loves to dance, and who had happened to be in the Holocaust, this was her victory.

There is a generational element to this kind of response. People just want to move on with their lives as normally as possible. It could be read as sweeping it under the rug. I know that my own parents don’t recognize their own traumas for what they are and it’s caused a lot of pain. So, ignoring it not the solution. But maybe there’s another way. A middle ground between making your trauma your identity and ignoring it completely. I don’t know the answer.

I’d been thinking for a while that I wanted to change the title of this newsletter. Yes, I am still angry at the System. Yes, I am still angry that my former pastor will never be held accountable for his actions. But this is not about him anymore. This is about me. This is about the kids like me who are still in that world and may be looking for a way out.

When I saw my work bound together for the first time, I realized that the Not Your Helpmeet project was done. This doesn’t mean that I won’t keep writing about life after Fundamentalism. I can’t help but write about that, but that banner doesn’t serve me anymore.

Which brings us to ghosts, again. Ghosts have been following me around for years now. And it makes sense. We all have ghosts. These traumas that shape us but don’t define us. You can move on and make a new life for yourself, yet those past selves and past experiences will always be hovering in the periphery. These are the everyday ghosts.

Last year, I set a goal to write every week, but that is really not a sustainable way to write when it’s not your full-time job. My goal this year is to write twice a month, which, hopefully, will give me more time to write more thoughtful/researched pieces than I did last year. Thanks, as always, for reading along.

I really enjoyed reading your post. Please let me know how I might obtain a copy of your new book. It must be pretty exciting to see your essays in a formal, professional looking book!

On another note, I feel the same way about my non-religious upbringing as you do about your religious one. It doesn’t really suit me anymore but I always have to keep coming back to it! I wish you well in your career and your blog writing.